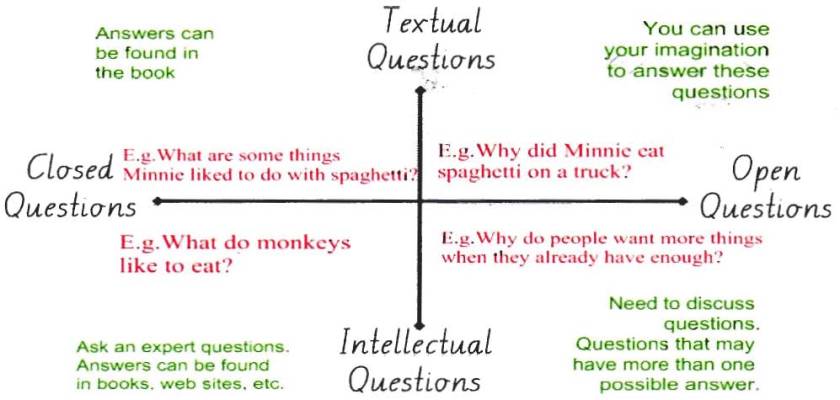

James Nottingham presents the above useful diagram and a commentary on his blog;

He says;

To go to James’ blog click HERE

James Nottingham presents the above useful diagram and a commentary on his blog;

He says;

To go to James’ blog click HERE

A set of presentations in French or English on Philosophy for Children and allied subjects is available HERE

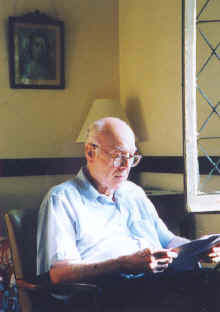

Ann-Margaret Sharp is interviewed here by Saeed Naji. Ann-Margaret is the chief collaborator with Professor Matthew Lipman in the development of the Philosophy for Children (PFC) programme

Ann-Margaret Sharp is interviewed here by Saeed Naji. Ann-Margaret is the chief collaborator with Professor Matthew Lipman in the development of the Philosophy for Children (PFC) programme

Ann Margaret Sharp, the “grand-old-lady” of the Lipman-school, is one of the main characters in the IAPC organisation, and has collaborated with founder Matthew Lipman for many years. She has written philosophical short-stories for children, and has also contributed to several of the teacher manuals.

Saeed Naji is a researcher at the Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies in Tehran, Iran, cfr. http://www.ihcs.ac.ir/. Naji interviewed Ann Margaret Sharp on a P4C-conference in San Cristobal de las Casas, Mexico, on February 26th, 2004. Many thanks to Saeed for letting us publish this interview. Visit Naji’s Iranian P4C-pages: www.p4c.ir

John Dewey was wont to remind educators that there is a big difference between the logical development and presentation of a discipline and the psychological, developmental presentation of a discipline.

The philosophical text is an attempt to present philosophy in a logical and comprehensive manner devoid of experience. The philosophical story-as-text is an attempt to motivate children to inquire into philosophical concepts and philosophical procedures in a way that is directly related to children’s experience. In other words, the narrative presents philosophy embedded in the experience of fictional characters.

Children enjoy stories and can be motivated by them to think and inquire if the stories focus on issues and event which they find intriguing and contestable, while remaining connected to their own daily experience. When a story is discussed by a group of children it becomes a vehicle over which children, rather than adults, have control. Unlike the traditional textbook, it is their story and they use it to set an agenda for discussion and philosophical inquiry.

But there is a further reason for using narrative when working with children. We cannot assume that children walk into the classroom able to do philosophy well. They need to know how to proceed, and one effective way to help them acquire this procedural knowledge is to involve them, intellectually as well as emotionally, in the lives of characters who enact and model the processes of inquiry. These characters do not have to be the heroes, heroines and villains one finds in many literary children’s classics, but can be presented as ordinary children much like themselves. These fictional children take up the struggle of articulating what constitutes a good reason, or a good analogy or a good distinction or of examining the assumptions and implications of what is said. By what they think, say and do, they show that they care about ideas and value good thinking–even if they do not always exemplify it in their own behavior. If we can encourage children to identify with the intellectual processes of these characters, then they too will begin to practice these procedures of good inquiry and come to value them.

This view of narrative as a preparation for and a stimulus to children doing philosophy matches, in part, Martha Nussbaum’s account of the relationship between moral education, ethical judgment and narrative… Noting that philosophy must be directed to practical as well as theoretical concerns, Nussbaum, in her Loves Knowledge, makes a compelling case for approaching ethical judgment–making via the particular lives and complex predicaments of fictional characters:

Without a presentation of the mystery, conflict and riskiness of the lived deliberative situation, it will be hard for philosophy to convey the peculiar value and beauty of choosing humanly well… It is this idea that human deliberation is constantly an adventure of the personality, undertaken against terrific odds and among frightening mysteries, and that this is, in fact, the source of much of its beauty and richness, that texts written in traditional philosophical style have the most insuperable difficulty conveying. (p. 142)

All children are engaged in an adventure of making better judgments (whether they realize it or not). This involves thinking, critical, creative and caring thinking, about many aspects of human experience that are not tapped by traditional philosophy textbooks. Children who are in the process of building their own communities of philosophical inquiry will use stories as a springboard or trigger for their own further inquiry. What begins as reflection on a puzzling concept in a story will move to a consideration of questions and ideas which come from the children’s own experience. The stories themselves constitute a vehicle for young persons to gain access to the realm of philosophical inquiry in such a way that they can see the connection between their on-going inquiry and their making of better judgments in their daily lives.

To read the full interview go HERE

Professor Matthew Lipman – founder of Philosophy for Children (PFC)

.

Videos of PFC Philosophy for children

NB – I have been asked by Dr McCall to point out that ALL the videos are HERS not Prof. Lipman’s – and there was me thinking that she had learned PFC from Lipman!

.

Lots more on YouTube under ‘Philosophy for Children’

As years go by, even from an early age, we all make adjustments, we all accommodate, we all shift to make ourselves more comfortable.

The UK Guardian newspaper online carried a wonderful article, and an even more wonderful photograph, about a shift in the life of Tom Leppard, the leopard man of Skye, now that he’s 73.

Tom Leppard the leopard man of Skye. Photograph: Murdo Macleod

The article tells us that;

The leopard man has been domesticated. After 20 years of living in the wilds on a remote part of Skye, the man made famous for his leopard tattoos has changed his spot for a one-bedroom apartment. At 73, Tom Leppard was starting to feel his age, and the weekly kayak trip across the fast-flowing Kyles of Lochalsh for supplies was taking its toll. He was “one big wave away from disaster”, and when a friend offered him the chance to leave the shore of Loch na Bèiste for the comfort of four walls in the village of Broadford, he leapt at the chance.

So Tom Leppard has shifted to new accommodation.

The brilliant article and even more brilliant photograph leave me with two lines of thought that I would like to follow up in subsequent posts.

The first line of thought is about all those dualities that we have to balance and adjust to maintain our sense of who we are. There are many – here are just a few; me-not me, my space-not my space, embrace-intrusion, willed change v. forced change, now-not now, my identity as derived from my memories-the terror of not being, identifying with v. dis-identifying with, being inside v. being outside, a sense of perfect place v a sense of alienating place, my group-not my group, being part of a salad v. being part of a soup, and many, many more.

All of these dualities around the issue of identity go much further and deeper when we compare and contrast this discussion with the pereenial nowness, no-dual philosophy of such writer-teachers as Ken Wilber or Eckhart Tolle.

The second line of thought concerns the genius of the photograph per se.

Both lines of thought I see as fascinating for philosophical inquiry and creativity lessons with children or adults – starting with this article and photograph.